What does having a strong core mean?

Have you ever heard: “Why do I have abs, but no strength in my core? Or why do I have strength in my core, but no abs?” There is a lot of confusion around what ‘having a strong core’ actually means… so let’s explore more about ‘what is the core’.

Author / Peter Qiu

The history behind the word ‘core’

The concept of ‘core stability’ probably originated from Australian research on postural control for both healthy and chronic low back pain (CLBP) patients. The researchers were interested in the role of the motor system — how the nervous system organizes the appropriate responses to support the spine, give us postural control to counteract gravity and balance while at the same time, also co-coordinating important functions such as breathing and continence. The evidence suggests that when spinal pain is present, the strategies used by the central nervous system may be altered.

Much of their research involved studying the feedforward anticipatory role played by the intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) mechanism, an important aspect of the antigravity postural control and spinal stabilization system.

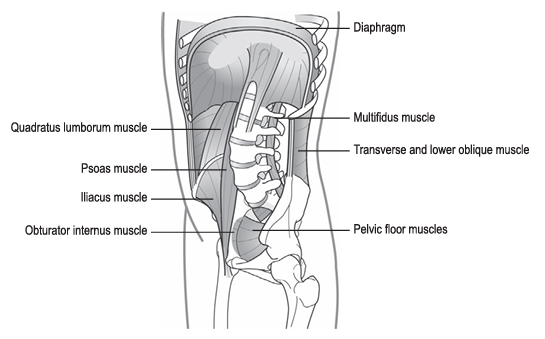

They studied the roles of various muscles contributing to a synergy of muscles responsible for generating intra-abdominal pressure (IAP), namely the: transversus abdominis, the diaphragm, the pelvic floor muscles (PFM) and lumbar multifidus.

Hence it is appropriate to adopt the term ‘stabilization synergy’. This affords natural control from inside the ‘core’ of our being.

‘Core’ functional mechanisms

In essence, healthy antigravity postural support and spine—pelvic movement control can be distilled as consisting of three inter-dependent functions:

1. The breathing mechanism — which plays a fundamental role in the generation of IAP.

2. Postural control mechanisms of the axial column — a duality of:

Balanced yet adaptable co-activation between the axial flexor and extensor muscle systems and appropriate levels of IAP for postural support.

3. Sound postural-movement control of the proximal limb girdles — particularly the pelvis as its control directly influences trunk flexor/extensor activation patterns.

Next, let’s take a look at

the three most important core muscles:

The diaphragm: the forgotten element in ‘core control’?

Long acknowledged as ‘the’ principal muscle of respiration, it’s also important in postural control through its contribution to the generation of IAP

As the crura are attached between T12 to L2-3 the diaphragm directly affects upper lumbar stiffness. Experimental stimulation of the diaphragm without concurrent activity of the abdominal or back extensor muscles creates an extensor torque in the spine. When respiratory demand is substantially increased (during hypercapnia (an increase in partial pressure of carbon dioxide), taxing exercise, or respiratory disease) respiration wins over postural control. The diaphragm (and transversus and the PFM) show diminished restorative activity and postural IAP may be degraded.

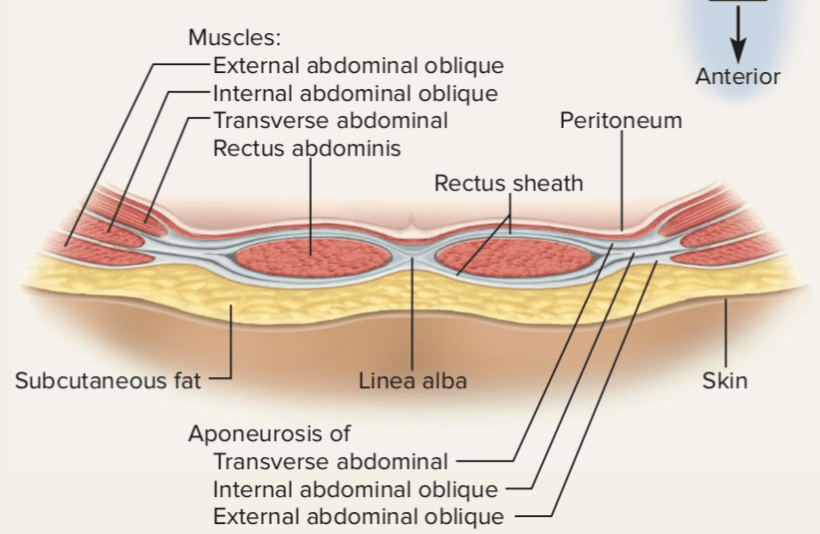

The abdominal muscles: more than just flexors

Postural tension and respiratory studies suggest that there is independent control between the deeply placed transversus and the more superficial abdominals — the obliques and rectus abdominis. Transversus activates in advance of the superficial abdominals and is more stimulating yet adaptively involved in the generation and modulation of IAP for the fluctuating demands of respiration and postural control

However, this differential function between the deep and superficial abdominals is generally overlooked by coaches. Instead of specific activation and building control and endurance in the deep ‘stabilizing synergy’ to support ‘uprightness’, much of the ‘core training’ offered simply becomes ‘strengthening the abs’ as a group — principally the superficial abdominals. This typically looks like lying in a supine position with repeated cycles of spinal flexion, such as crunches, curls, sit-ups, etc. This places predictable adverse consequences on the discs and spinal health and wellbeing. In actuality, we should emphasize the deep abdominals— the transverse abdominis.

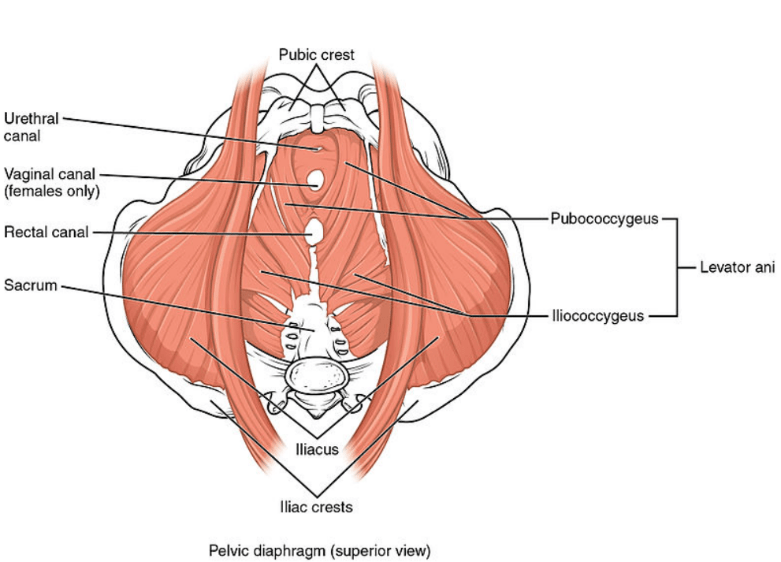

The pelvic floor: the seat of breathing and postural control

The PFM must contract during tasks that elevate IAP to both contribute to pressure increase and to maintain continence. If you don’t breathe well and maintain strong posture, you are more likely to get CLBP and develop incontinence.

Upright unsupported sitting postures recruit greater PFM activity than slumped supported postures. Resting PFM activity is also higher in standing and is affected by the lumbo-pelvic posture being highest in a hypo-lordotic posture —— not necessarily a good thing as continence disorders have been linked to increased PFM and external oblique activity (Smith et al., 2007a,b). Over-training the PFM and abdominals can be detrimental!

The PFM also contribute to intrapelvic biomechanics. Bear in mind that their (over) activity counterbalances the sacrum and coccyx which places the sacroiliac joint in its less stable position. The ability to eccentrically lengthen the PFM is important in ‘fundamental patterns of pelvic control’ which support healthy axial control mechanisms.

In reality, our ‘8-pack’ is actually made up as a 29 pack of core muscles, but the groups of core muscles talked about today – transversus abdominis, the diaphragm, the pelvic floor muscles (PFM) and lumbar multifidus – are very important. Hopefully, in the future, we will not neglect their activation during training, so that we can stay away from low back pain.

本篇文章來源于微信公衆号: 上海優複康複醫學門診部